Month: January 2022

Thin Lizzy – Fight or Fall

Slick Rick – Why, Why, Why

The Raincoats – No One’s Little Girl

Beck – Debra

Carambolage – Gehirnwäsche

JJ Cale – Wish I Had Not Said That

Yura Yura Teikoku – Robot Deshita

D Train – You’re The One For Me

Warp 9 – Nunk

Address of the International Working Men’s Association to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America

Presented to U.S. Ambassador Charles Francis Adams

January 28, 1865

Sir:

We congratulate the American people upon your re-election by a large majority. If resistance to the Slave Power was the reserved watchword of your first election, the triumphant war cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery.

From the commencement of the titanic American strife the workingmen of Europe felt instinctively that the star-spangled banner carried the destiny of their class. The contest for the territories which opened the dire epopee, was it not to decide whether the virgin soil of immense tracts should be wedded to the labor of the emigrant or prostituted by the tramp of the slave driver?

When an oligarchy of 300,000 slaveholders dared to inscribe, for the first time in the annals of the world, “slavery” on the banner of Armed Revolt, when on the very spots where hardly a century ago the idea of one great Democratic Republic had first sprung up, whence the first Declaration of the Rights of Man was issued, and the first impulse given to the European revolution of the eighteenth century; when on those very spots counterrevolution, with systematic thoroughness, gloried in rescinding “the ideas entertained at the time of the formation of the old constitution”, and maintained slavery to be “a beneficent institution”, indeed, the old solution of the great problem of “the relation of capital to labor”, and cynically proclaimed property in man “the cornerstone of the new edifice” — then the working classes of Europe understood at once, even before the fanatic partisanship of the upper classes for the Confederate gentry had given its dismal warning, that the slaveholders’ rebellion was to sound the tocsin for a general holy crusade of property against labor, and that for the men of labor, with their hopes for the future, even their past conquests were at stake in that tremendous conflict on the other side of the Atlantic. Everywhere they bore therefore patiently the hardships imposed upon them by the cotton crisis, opposed enthusiastically the proslavery intervention of their betters — and, from most parts of Europe, contributed their quota of blood to the good cause.

While the workingmen, the true political powers of the North, allowed slavery to defile their own republic, while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master, they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor, or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation; but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes. They consider it an earnest of the epoch to come that it fell to the lot of Abraham Lincoln, the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world. [B]

Signed on behalf of the International Workingmen’s Association, the Central Council:

Longmaid, Worley, Whitlock, Fox, Blackmore, Hartwell, Pidgeon, Lucraft, Weston, Dell, Nieass, Shaw, Lake, Buckley, Osbourne, Howell, Carter, Wheeler, Stainsby, Morgan, Grossmith, Dick, Denoual, Jourdain, Morrissot, Leroux, Bordage, Bocquet, Talandier, Dupont, L.Wolff, Aldovrandi, Lama, Solustri, Nusperli, Eccarius, Wolff, Lessner, Pfander, Lochner, Kaub, Bolleter, Rybczinski, Hansen, Schantzenbach, Smales, Cornelius, Petersen, Otto, Bagnagatti, Setacci;

George Odger, President of the Council; P.V. Lubez, Corresponding Secretary for France; Karl Marx, Corresponding Secretary for Germany; G.P. Fontana, Corresponding Secretary for Italy; J.E. Holtorp, Corresponding Secretary for Poland; H.F. Jung, Corresponding Secretary for Switzerland; William R. Cremer, Honorary General Secretary

Ambassador Adams Replies

Sir:

I am directed to inform you that the address of the Central Council of your Association, which was duly transmitted through this Legation to the President of the United [States], has been received by him.

So far as the sentiments expressed by it are personal, they are accepted by him with a sincere and anxious desire that he may be able to prove himself not unworthy of the confidence which has been recently extended to him by his fellow citizens and by so many of the friends of humanity and progress throughout the world.

The Government of the United States has a clear consciousness that its policy neither is nor could be reactionary, but at the same time it adheres to the course which it adopted at the beginning, of abstaining everywhere from propagandism and unlawful intervention. It strives to do equal and exact justice to all states and to all men and it relies upon the beneficial results of that effort for support at home and for respect and good will throughout the world.

Nations do not exist for themselves alone, but to promote the welfare and happiness of mankind by benevolent intercourse and example. It is in this relation that the United States regard their cause in the present conflict with slavery, maintaining insurgence as the cause of human nature, and they derive new encouragements to persevere from the testimony of the workingmen of Europe that the national attitude is favored with their enlightened approval and earnest sympathies.

I have the honor to be, sir, your obedient servant,

Charles Francis Adams

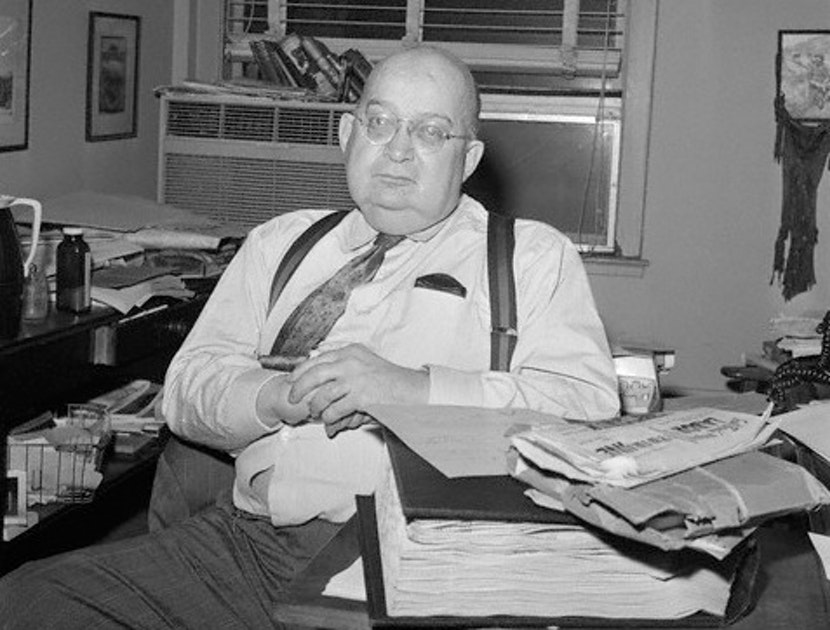

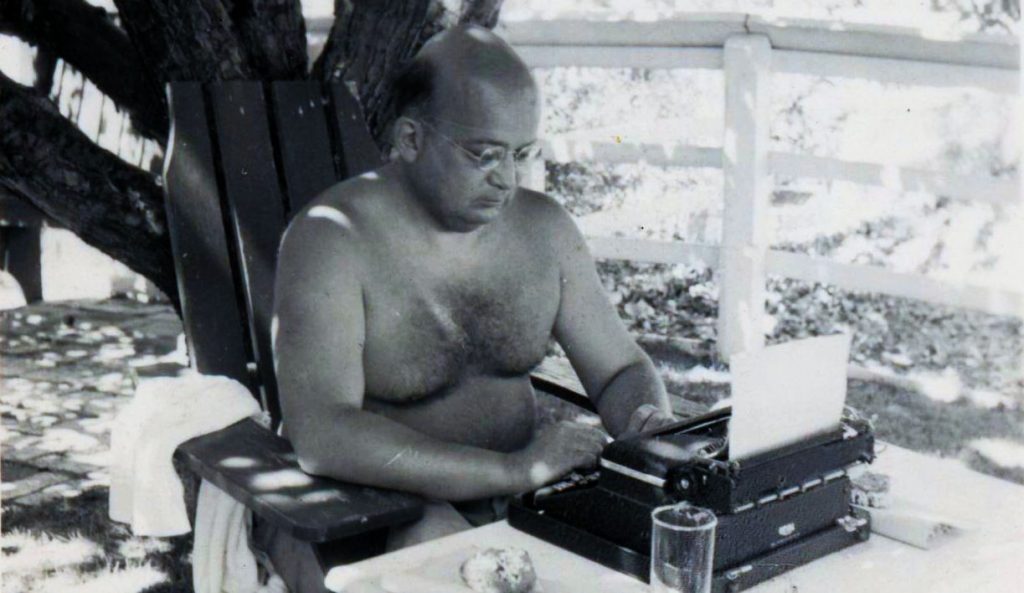

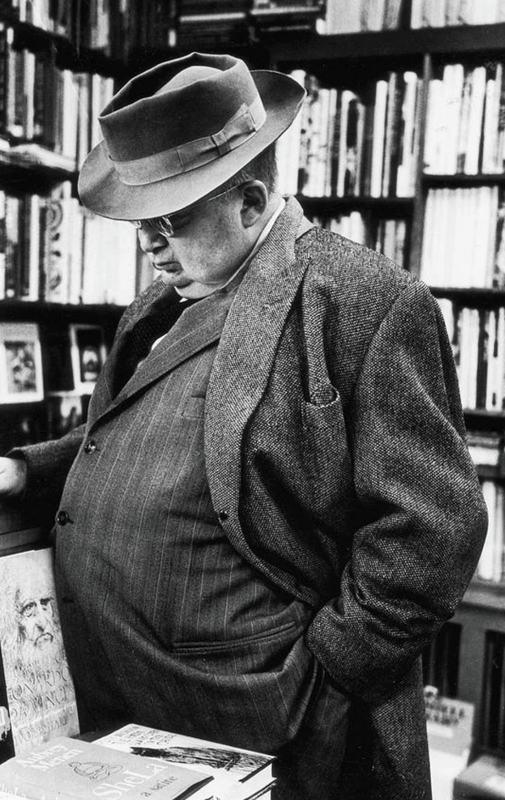

A.J. Liebling Obituary

“I used to be shy about ordering a steak after I had eaten a steak sandwich,” he once said, “but I got used to it.”

A.J. Liebling, a critic of the daily press, a chronicler of the prize ring, an epicure and a biographer of such diverse personages as the late Gov. Earl Long of Louisiana and Col. John R. Stingo died yesterday at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Mr. Liebling, who was 59 years old, entered the hospital on Dec 19, suffering from bronchial pneumonia.

In 1935, after about a decade of intermittent employment as a newspaperman. Mr. Liebling went to work for The New Yorker. Since then he had written hundreds of articles for the magazine, many of which later appeared in book form.

He first came to prominence as The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent on the eve of World War II. Later he followed the First Infantry Division across North Africa and into northern France. Despite chronic gout, a degree of plumpness and extreme nearsightedness, he regularly accompanied combat patrols.

In 1946, he took over the magazine’s “Wayward Press” department, first conducted by Robert Benchley. His perceptive, sardonic articles on such subjects as editorial campaigns for the end of meat price controls, news treatment of the Alger Hiss trial, and, more recently, the newspaper strike here, were widely read.

He resided in Chicago for a while in the late 1940’s, and the resulting dissection, published in 1952 as “Chicago: The Second City,” still possesses the power of creating instant rage there.

He considered Carl Sandburg’s poetic evocation of a brawling, enterprising city outmoded. Mr. Liebling said its cry had changed from “Let me at him!” to “Hold him offa me,” and suggested that the appearance of the city indicated it has been “plopped down by the lakeside like a piece of waterlogged fruit.”

In an extended New Yorker profile that appeared in book form in 1953 as “The Honest Rainmaker,’ he told of Hames A. Macdonald, a man of many occupations who was at the time a racing columnist for The New York Enquirer und the pen name of Col. John R. Stingo. The colonel, now deep in his 80’s, is still a familiar figure in midtown cafes.

Perhaps Mr. Liebling’s most widely read book was “The Earl of Louisiana,” which appeared in 1961, and was based, as usual, on a series of New Yorker pieces. Mr. Liebling took the rather unorthodox view that Governor Long, better known for his eccentricities, was the South’s most effective liberal in recent years.

He had been an amateur boxer in his youth, although, as he observed, he was not in the Ernest Hemingway class for size, skill or literary attainment, This interest was reflected in accounts of major prizefights and sketches of ring personalities that appeared from time to time in the magazine.

He studied ancient history at the Sorbonne, without much dedication, and became a scholar of the bistros and cafes.

A collection of his articles on boxing, titled “The Sweet Science,” was published in 1956

In the middle fifties he revisited the old battlegrounds of the First Division, reacquainting himself with the delights of Calvados and Norman delicacies he described in loving detail in “Normandy Revisited,” which appeared in 1958.

In “Between Meals,” published last year, Mr. Liebling cast an unaccustomedly tender eye on his growing up in Manhattan, trips to Europe with his parents as a child and his own student days in Paris in the early twenties.

In October of this year, “The most of A.J. Liebling,” a selection from a dozen of his earlier collections, was published.

Mr. Liebling never lost the reporter’s skill of recording facts accurately, but as his style matured it became convoluted, subtle and abounding in unlikely allusions. An account of a Sugar Ray Robinson fight, for example, might be a delicate embroidery on a theme suggested by a medieval Arabian historian to whom he was partial.

Mr. Liebling bore the marks of the gourmet: an extended waistline and rosy cheeks. “I used to be shy about ordering a steak after I had eaten a steak sandwich,” he once said, “but I got used to it.”

Abbott Joseph Liebling was born in New York on Oct. 18, 1904. His father, Joseph Liebling, was a furrier. The son later described him as embodying the Horatio Alger legend in reverse, making his money early and dying broke.

The Son, who was generally known as Joe, was expelled from Dartmouth College for refusing to attend chapel. He enrolled at the School of Journalism at Columbia University, which he later said, had “all the intellectual status of a training school for the future employees of the A. & P.”

Last May, though, on the school’s 50th anniversary, he was one of 81 persons honored as distinguished alumni.

His first job after graduation was in the sports department of The New York Times. One of his jobs was to compile basketball box scores, right down to the name of the referee. One night Mr. Liebling failed to get the official’s name from a high school correspondent and gave it as “Ignoto,” which is Italian for “unknown.”

Deciding he was on to a good thing, Mr. Liebling stopped asking for the referee’s name. In the weeks that followed, Ignoto appeared at games all over the East Coast, sometimes several in a night. The sports editor made inquiries. He didn’t see the joke, and eight months after being hired, Mr. Liebling was dismissed.

He went next to The Providence (R.I.) Journal and Evening Bulletin, where as a reporter and feature writer, he later said, “I oozed prose over every aspect of Rhode Island life.”

In all he spent four and a half years there, interrupted by a year in Paris. He arranged to have his father finance the trip by telling him that he was thinking of marrying a cotton broker’s mistress. There he studied ancient history at the Sorbonne, without much dedication, and became a scholar of the bistros and cafes.

He returned to New York in 1930. Not immediately finding employment, he hired a man to picket the entrance of The World, carrying a sign that read, “Hire Joe Liebling.” The city editor always used the back door, and it was not until the paper had gone out of business that Mr. Liebling caught on with the World-Telegram.

Mr. Liebling wrote hundreds of feature stories during the next five years and gained the familiarity with off-beat New York that he continued to The New Yorker.

He remained active until he entered the hospital a week ago, working on a study of the reaction of the southern press to the assassination of President Kennedy.

Despite the considerable breadth of his published works, it is likely that Mr. Liebling most enjoyed his role as a press gadfly. His favorite themes were the diminishing competition and consequent loss of enterprise caused by merger and sales.

In 1948, when the fist collection of “Wayward Press” articles was published, Mr. Liebling dedicated it “To the foundation of a School for Publishers, Failing Which No School of Journalism Can Have Meaning.”

Mr. Liebling was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor by the French Government for his work as a writer on French subjects and as a war correspondent. He was the translator and editor of “The Voices of Silence,” a compilation of writings be members of the Resistance during World War II.

He lived at 45 West 10th and had a summer home at Easthampton, L.I.

He is survived by his widow, Jean Stafford, the novelist, whom he married in 1959, and a sister, Mrs. Harold Stonehill. Two previous marriages, to Ann Beatrice McGinn in 1934 and to Lucille Hille Spectorsky in 1949, ended in divorce.

Funeral services will be held at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Church, Madison Avenue and 81st Street, at 1 P.M. tomorrow.